Book review: Erik Satie Three Piece Suite by Ian Penman

An enjoyable meander through the eccentric French composer's life and influence

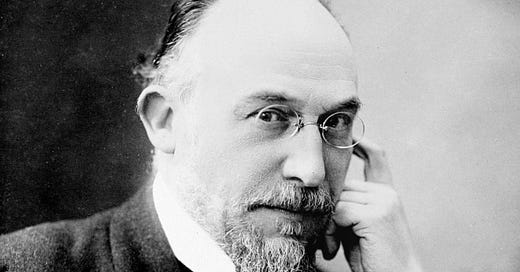

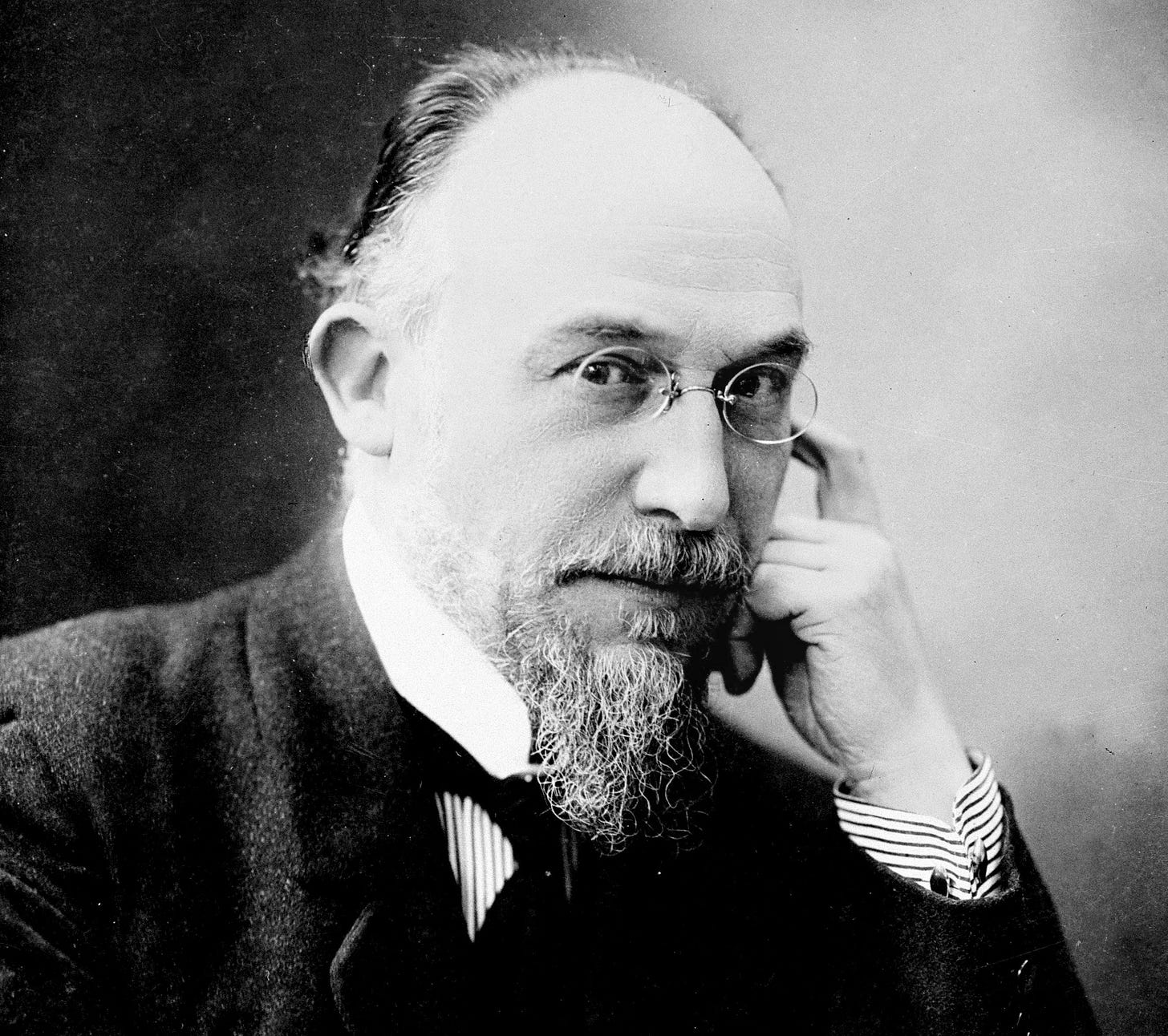

(Photo of Erik Satie, 1920 by Henri Manuel)

“How you start a piece on Erik Satie, it transpires, is with the phrase How to Start a Piece on Erik Satie.” And so this quote three-quarters of the way through Ian Penman’s book on the French composer and pianist (1866-1925) gives me my opening.

Penman is a British writer, music journalist and critic (he began at the NME in 1977) and author of the award winning Fassbinder: Thousands of Mirrors (2023). This latest book is not a conventional biography as much as a meander through Satie’s life and influence and Penman’s own Satie related musings. It’s no less enjoyable for that.

The book is structured in three parts: an opening Satie Essay, an encyclopaedic Satie A-Z, and a Satie Diary (from 1.11.22 to 10.8.24).

The Satie Essay is the most conventional section of the book in that it is a biographical narrative. Here Penman highlights the ubiquity of Satie’s most famous pieces, the Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes, written in his early twenties, music that many know even if they don’t know the composer.

Much of Satie’s work consists of piano miniatures such as these although he also wrote two ballets, the symphonic drama Socrate, music for the 1924 silent French Dada film Entr'acte (a description of which starts Penman’s book) as well as his "furniture music", musique d’ameublement, a precursor of ambient music.

His influence was considerable, not least because he also mixed with some of the most significant artistic figures of the early 20th century including composers (Debussy, Poulenc and Milhaud); artists (Picasso, Duchamp and Man Ray); writers (Cocteau and Apollinaire) and film-makers (Picabia and René Clair).

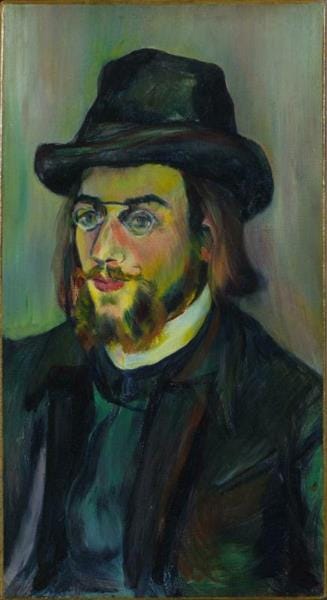

We also learn of Satie’s six month love affair - a “firework burst of passion” - with artist (and trapeze artist!) Suzanne Valadon who, amongst other things, painted a Portrait of Erik Satie (1893) and is the central figure in Renoir’s painting The Umbrellas (circa 1880-1886).

(Left: Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s The Umbrellas (c 1881-6) featuring Suzanne Valadon carrying hatbox; Right: Suzanne Valadon’s Portrait of Erik Satie (1893)

Satie was one of the most elusive and eccentric of early 20th-century composers. One doesn’t have to dive too deep before coming across references to his identical suits, stiff collars, bowler hats and umbrellas. We also learn that none of those in Satie's circle knew that he lived “on the rim of indigence” until his room was cleared out upon his death.

Satie, who was a lifelong heavy drinker, died at the age of 59 of cirrhosis of the liver. However, Penman also reports that there are no anecdotes about him being the worse for drink. In fact he includes Satie in a list of alcoholic twentieth-century artists who “bedevilled by drink, they still write or sing or play like angels. The opposite of sloppy: every note or word in exactly the right place”.

There are several other common themes weaving through the book, these include charity shops (whose “marvellous serendipity” is often a source of some of Penman’s favourite musical discoveries), dreams (“The 'Charlie Parker yes, Duke of Edinburgh no!' dream” sounds fascinating but alas that’s all we get to hear about it) and Flann O’Brien (who on more than one occasion is referenced in respect of Satie’s humour (“discovering Satie’s writing is like reading Flann O’Brien for the first time”). Satie's musical directions (e.g. “don't eat too much", "even duller if you can") are legendary.

One of Satie’s most famous pieces, by reputation if not by recognition, is Vexations, a single eighteen-note theme, without time or key signature, repeated. It was not published in his lifetime but gained attention through a marathon performance lasting over 18 hours on 9 September 1963 in New York, featuring a relay team of pianists including John Cage (who unearthed it in the late 1940s) and John Cale (before he joined the Velvet Underground).

The length and repetition are on account of the piece bearing the following instructions: “In order to play the motif 840 times in succession, it would be advisable to prepare oneself beforehand, and in the deepest silence, and the most serious immobility”.

But Penman goes on to suggest - there are 21 separate entries for VEXATIONS in the A-Z - “that it is posed as a possibility, not a command” and that “to take it at its word might mean to never play it at all. Or to play it entirely inside your own head. Everyone their own Satie”.

There is, however, an entry in the A-Z section which did irk me somewhat. Here it is:

PIANISSIMO (1)

A few favourite pianists: Paul Bley, James Booker, William Eggleston, Bill Evans, Glenn Gould, Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, Phineas Newborn, Bud Powell, Francis Poulenc, Erik Satie, Stan Tracey. What could they possibly have in common, other than the piano? Is there something odd lurking just under its keys, lid or seat?…And I can't help but notice all these piano men are... men. Is there something else going on here?

This had me immediately writing the following in reply:

Let me help you with that:

PIANISSIMO (2)

A few favourite pianists (all of whom I have been lucky enough to see perform live): Carla Bley, Martha Argerich, Mitsuko Uchida, Irène Schweizer, Zoe Rahman, Angela Hewitt, Khatia Buniatishvili, Imogen Cooper, Myra Melford, Maria João Pires, Yuja Wang, Hélène Grimaud.

It should be noted that later in the diary section of the book Penman states “Torn over whether to include Carla Bley in my list of favourite pianists” (10.7.24) and notes that Irène Schweizer is one of “three pianists new to me, via social media…Whole worlds remain to be explored” (31.7.24). He also states “Hard not to notice that large percentage of the best Satie/Debussy/Ravel interpreters are women” (12.7.24). (The video link to Gymnopédie No.1 above will take you to a performance by Khatia Buniatishvili.)

Penman, on more than one occasion, refers to people querying his musicological bona fides - “I hold my hand up to patches of technical ignorance” - but as he then rightly goes on to say, “there are other considerations involved”. And this is where the book comes into its own. It captures a wonderful distinctiveness that is revealing of both the composer and the author.

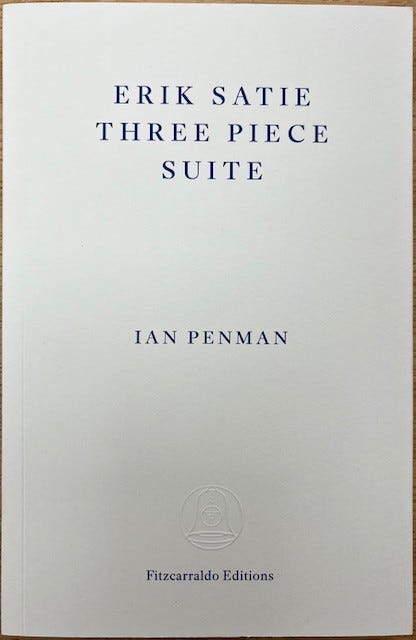

Erik Satie Three Piece Suite

by Ian Penman

Fitzcarraldo Editions 2025 (paperback 224 pages, ISBN: 9781804271537)

For more information on the book and to explore purchase options, visit the Fitzcarraldo Editions website.